By D.A. King

By D.A. King

The below statements and remarks were collected on Friday, March 15 and Saturday, March 16, 2024.

__

Statement on HB 1105 as amended in the Georgia Senate committee process from former Gwinnett County Sheriff Butch Conway – March 16, 2024

I write a note to thank Rep. Petrea for sponsoring HB 1105 and to express my educated and experienced support for the intent of important legislation. It is glaringly obvious that we have sanctuary counties in Georgia and sadly, this dangerous fact has been a well-kept secret despite the years-long efforts of Mr. D.A. King to expose the dangerous situation.

The current Senate language in HB 1105 can arguably be seen as essentially ensuring that ICE detainers are outlawed in the entire state of Georgia. The Senate version totally changes the intent of the House bill and will protect criminal aliens doing harm to our communities and the Sheriff’s whose intent is to keep them in our communities. Shame on them.

Perhaps nowhere in the state is a strong version of HB 1105 needed more than here in Gwinnett County where the current sheriff has made at least one public announcement that he has no intention of compliance with either OCGA 42-4-14 or OCGA 36-80-23. I am aware of the responses to open records requests that indicate our sheriff has followed through on his policy.

I have known for some time that a powerful lobbying concern is pushing for changes to the procedures and penalties written into the bill. Now I see that a Senate committee has capitulated to the demands of that lobbying effort.

I urge all concerned to reject the amendments made in Senate Public Safety committee.

ICE detainers are issued and signed under authority of multiple federal laws and are the source of great fear on the part of criminal illegal aliens. Whether or not it is an intentional move to ensure no illegal alien is ever picked up by ICE from a Georgia jail, the change to HB 1105 that would require a criminal arrest warrant signed by a judge or magistrate would have that effect.

I was proud to use the 287 (g) program in the Gwinnett jail. Use of that program saved lives and tax dollars because it represented a clear promise to criminal aliens that we were serious about encouraging federal authorities to take custody of the illegal aliens who landed in our jail because of an arrest for violation of Georgia laws.

Until my retirement at the end of 2020, I was proud to serve in law enforcement for forty years, first with the Gwinnett County Police Department, then seven years as a magistrate judge, five years as Chief of Police in Lawrenceville and then 1997 – 2020 as Gwinnett County Sheriff.

Please feel free to contact me if I can be of any more assistance. Please feel free to distribute this note as you may find useful.

Best regards,

Butch Conway

Dacula

_____

STATEMENT BY TOM HOMAN ON THE SENATE VERSION OF HB 1105

Mr. Homan is a former police officer and government official who served during the Trump Administration as Acting Director of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The proposal of the Georgia Senate Public Safety committee that detainers not be complied with without a judicial warrant is based on a misunderstanding of both the Constitution and the nature of immigration detainers.

The Fourth Amendment protects “the people” from “unreasonable” searches and seizures. It seems obvious that citizens of foreign countries who have entered our country illegally are not part of the people of the United States. For example, courts have held they have no right to own firearms, because the Second Amendment protects “the right of the people to keep and bear arms.” So, to be blunt about it, illegal aliens probably don’t have Fourth Amendment rights to begin with. They are citizens, just not of this country.

But it’s not as if we want to do anything unreasonable to illegal aliens anyway. In fact, even if illegal aliens did have Fourth Amendment rights—if the amendment were not limited to “the people”—there would be nothing in the Constitution against federal officers’ detaining them on probable cause to believe they are in the country unlawfully. And nothing against state officers’ cooperating in that detention based on that probable cause.

That’s because these things are reasonable. In fact, they are necessary for a functioning system. Every country in the world, including ours, has a civil immigration system, not a criminal one. Illegal aliens are detained, pending their removal, because they are not supposed to be here in the first place, not because they have committed a crime (though often they have). Detaining illegal aliens is nothing else than securing the border, at a physical distance from the border. And it is completely reasonable, under the Fourth Amendment, to detain them on a probable cause showing that they have committed the civil offense of being in the country unlawfully. It’s been done that way since the founding of our country. And it is reasonable, as it is always reasonable in other contexts, for state law enforcement to cooperate with federal law enforcement based on that probable cause.

The Georgia Senate wants a requirement of a judicial warrant before state jailers can cooperate in immigration detention. That would needlessly gum up the process and make this law ineffective. Judges are not well-placed to decide whether there is probable cause to believe an alien is in the country unlawfully. If called upon to decide that, a judge would have to ask ICE, and rely on ICE’s databases. And asking a judge to issue a criminal warrant based on probable cause to believe a crime has been committed would always result in a denial in this context—just because the offense is civil, not criminal. And civil warrants, such as ICE detainers, are traditionally issued by administrative agencies, not courts. ICE has the pertinent data here and is best positioned to make this initial determination of probable cause.

Our immigration system was carefully constructed. It is time-tested, and legal. It is past time to help sheriffs and other state law enforcement do their duty to protect our people from the increasingly dangerous illegal aliens that are being flooded into our country. Securing the border—and that’s what this law helps do—saves lives, now more than ever.

Tom Homan

_____

Response to changes to HB 1105 in the senate Public Safety Committee on March 14 from ‘Hart Celler’ – a nom de plume for an active U.S. Federal immigration enforcement agent. See @8USC12 on Twitter/X.

“Any law which would require the production of an almost unobtainable document rather presumably to ensure due process for aliens and/or prevent lawsuits alleging violations of aliens’ rights does nothing to further public safety of Georgians any more than being a sanctuary encourages unlawfully present crime victims or witnesses to report crimes. The aliens ICE requests continued detainment of, pending transfer to Federal custody have already committed a crime in Georgia in violation of reasonable expectations regarding order and discipline necessary for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Of 20,127 criminal cases in FY 2023 for the two most common criminal immigration offenses, 8 U.S.C. § 1325(a) and 1326, only 84 occurred in Georgia, and the majority, 61 were in the Northern District of Georgia for the latter, which is an offense where an alien has returned to the United States after having been previously deported.”

_____

Email (copied to us) sent to Senator John Albers, Chairman of the Senate Public Safety Committee by Bob Trent in St. Mary’s, GA. Mr. Trent is a former Border Patrol agent, former INS agent and retired Assistant Director, Enforcement Training, U.S. Immigration Officer Academy, Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, Glynco, GA.

I have just listened to the hearing you held yesterday on HB 1105 and I am blown away. You had a strong bill, until you removed the ICE detainer and replaced it with a requirement for a US Magistrate warrant. This pretty much neuters the bill.

I am a retired Senior Special Agent of the former US INS, with many years of immigration enforcement experience. In all of my years I have never heard of ICE (formerly Deportation Operations under INS) where obtaining a US Magistrate warrant.

All deportation/removal proceedings come under the Immigration & Nationality Act (1952), which makes the laws all administrative and not criminal.

The current wording all but shuts down any chance of ICE taking custody of criminal illegal aliens before they are released from jail.

Robert M. Trent, Senior Special Agent, USINS (Ret)

Saint Marys, Georgia

_____

Email received here March 15 from Jessica Vaughan at CIS

Hi D.A.,

This is my assessment of the proposed requirement that Georgia law enforcement agencies should refuse to comply with immigration/ICE detainers unless accompanied by a “judicial” or court-ordered warrant.

Any requirement for Georgia law enforcement agencies to demand a “judicial” or court-ordered warrant in order to hold aliens on an ICE detainer is unreasonable and will effectively shut down ICE’s ability to take custody of deportable criminal aliens upon disposition of their case or sentence. The so-called “judicial” warrant is a legal fiction in the context of immigration enforcement.

Federal immigration law authorizes ICE to issue detainers, which are in practice accompanied by a statement of probable cause that an alien is removable and a warrant of arrest or a warrant of removal. These ICE warrants are reviewed and approved by ICE supervisory officers. Neither immigration judges nor federal judges can issue such a warrant, and it is not required under federal law. With such a requirement, all law enforcement agencies would be required to release criminal aliens back to Georgia communities if ICE is not able to be present at the very moment of sentencing or release from jail or prison.

Congress provided ICE with the authority to issue detainers for the very purpose of making sure that those deportable aliens who have been arrested by local authorities can be placed into removal proceedings or removed if a judge has already issued a final order of removal, and so that they are not able to remain here in defiance of immigration laws, thereby protecting the community at large. If Georgia were to adopt this requirement, it would become a sanctuary state for criminal aliens.

I hope that is clear and meets your needs. I would be happy to discuss with any of the legislators. Regards, Jessica

Jessica M. Vaughan (BIO)

Director of Policy Studies

Center for Immigration Studies

(774)291-9005

@JessicaV_CIS

_____

Email received from George Fishman – former deputy counsel at DHS on March 15, 2024

D.A.,

I hope this helps:

I am the senior legal fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies. During the Trump administration, I served as a deputy general counsel at the Department of Homeland Security from 2018-2021 and also as acting chief counsel at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services from 2020-2021. I was the chief Republican counsel for the House Judiciary Committee’s immigration subcommittee from 1998 to 2018. I graduated from the University of Michigan Law School in 1988.

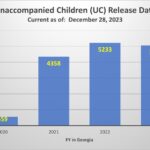

Detainers are notices issued by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other DHS units that ask local, State and Federal law enforcement agencies not to release suspected removable aliens held at their facilities for a short period in order to give ICE an opportunity to take them into its custody. They are a vital law enforcement tool for ICE, which issues thousands of detainers each month (and prior to the current administration issued over 10,000 most months). This chart was prepared by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University (https://trac.syr.edu/reports/719/):

ICE issues detainers under its administrative powers. There is absolutely no requirement or need for it to seek judicial warrants. In fact, it would be as a practical matter impossible for ICE to obtain unnecessary judicial warrants in the volume necessary to successfully carry out its law enforcement mission. Such a requirement would vitiate the effectiveness of detainers as an effective tool to take criminal removable aliens off of our streets and out of our communities.

George Fishman

Senior Legal Fellow

Center for Immigration Studies

202-525-9576

_____

Email received from the Center for Immigration Studies for Andrew Arthur – retired federal immigration judge – bio here.

D.A.: Just post this. It says it all.

Immigration Judicial Warrants Don’t Exist

Time to pull the sanctuary jurisdiction fig leaf

By Andrew R. Arthur on September 17, 2019

Of late, I have written a number of posts about sanctuary policies issued by jurisdictions that deny that they are sanctuaries. Part of their shtick is to assert that they would comply with detainer requests that are accompanied by “judicial warrants”. Of course in the immigration context, there is no such thing.

In this blog, I borrow freely from my colleague Dan Cadman, who wrote about a similar issue in July 2018. The points that Cadman made remain relevant, and bear repeating.

But first, the contentions. One of the sanctuary policies (and probably one of the worst ones I’ve ever heard of) comes out of Montgomery County, Md. It includes the following: “Immigration detainers, that are not accompanied by judicial warrants, are civil detainers for which the federal government bears sole responsibility.” I have no idea why the extra commas were included in that sentence, nor what exactly “sole responsibility” consists of. Immigration detainers are, however, civil detainers, because immigration proceedings are civil — as opposed to criminal — in nature. Immigration detention is, however, detention, and the authority for such detention has been recognized as valid since the 19th Century. read the entire education here.

_____

Observation received via text from Jon Feere,

Mr. Feere previously served in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as the Senior Advisor to the Director and as ICE’s Chief of Staff from January 2017 to January 2021.

ICE simply isn’t going to be seeking judicial warrants or any other sign-off from any other part of the government while issuing detainers – not under the Biden administration, not under the Trump administration, or under any administration. Congress made ICE the sole authority to issue detainers and chose not to pull any other part of the government into the process. Only sanctuary city advocates try to add levels of process, and they do so because they know it’s a way of undermining immigration enforcement. Any state policy that requires ICE to obtain permission to do its job is effectively a sanctuary policy.

_____

Line

270 – No person identified by the LESC of the United States Department

271 of Homeland security pursuant to this subsection shall de detained unless a request to

272 detain has been received pursuant paragraph (2) of this subsection or the existence of

273 an arrest warrant issued by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement

274 Division of the Department of Homeland Security a federal judge, or federal magistrate for each person verified.

By D.A. King

From the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington D.C.

Of late, I have written a number of posts about sanctuary policies issued by jurisdictions that deny that they are sanctuaries. Part of their shtick is to assert that they would comply with detainer requests that are accompanied by “judicial warrants”. Of course in the immigration context, there is no such thing.

In this blog, I borrow freely from my colleague Dan Cadman, who wrote about a similar issue in July 2018. The points that Cadman made remain relevant, and bear repeating.

But first, the contentions. One of the sanctuary policies (and probably one of the worst ones I’ve ever heard of) comes out of Montgomery County, Md. It includes the following: “Immigration detainers, that are not accompanied by judicial warrants, are civil detainers for which the federal government bears sole responsibility.” I have no idea why the extra commas were included in that sentence, nor what exactly “sole responsibility” consists of. Immigration detainers are, however, civil detainers, because immigration proceedings are civil — as opposed to criminal — in nature. Immigration detention is, however, detention, and the authority for such detention has been recognized as valid since the 19th Century.

No agent or department may arrest or detain a person based on an Administrative Warrant, an Immigration Detainer, or any other directive by DHS, on a belief that the person is not present legally in the United States or has committed a civil immigration violation.

As set forth below, detainers are not issued “on a belief that the person is not present legally in the United States or has committed a civil immigration violation”, but rather upon probable cause of those facts. That is simply an aside, however.

Not to be outdone by his neighbor to the south, on July 24, 2019, Baltimore County, Md., Executive John “Johnny O” Olszewski, Jr. (D) affirmed that an executive order captioned “Upholding Law Enforcement Standards on Immigration Status, Diversity and Equity”, issued by one of his predecessors, the late Kevin Kamenetz, remains in effect countywide. Paragraph 4 of that order states:

No personnel within the Police Department or Department of Corrections shall cause to be detained any individual beyond their court ordered release date, except upon reasonable belief of the existence of an order of detainer issued by a properly recognized judicial official. [Emphasis added.]

I have no idea what a “properly recognized judicial official” means in this context. As an immigration judge, I was properly recognized as a judicial official by the circuit courts, but it likely is intended to refer to a federal district court judge or federal magistrate.

Detainers are governed by 8 C.F.R. §287.7(a), which states:

Detainers in general. Detainers are issued pursuant to sections 236 and 287 of the [Immigration and Nationality] Act [INA] and this chapter 1. Any authorized immigration officer may at any time issue a Form I-247, Immigration Detainer-Notice of Action, to any other Federal, State, or local law enforcement agency. A detainer serves to advise another law enforcement agency that the Department seeks custody of an alien presently in the custody of that agency, for the purpose of arresting and removing the alien. The detainer is a request that such agency advise the Department, prior to release of the alien, in order for the Department to arrange to assume custody, in situations when gaining immediate physical custody is either impracticable or impossible. [Emphasis added.]

Also pertinent is 8 C.F.R. §287.7(d):

Temporary detention at Department request. Upon a determination by the Department [of Homeland Security (DHS)] to issue a detainer for an alien not otherwise detained by a criminal justice agency, such agency shall maintain custody of the alien for a period not to exceed 48 hours, excluding Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays in order to permit assumption of custody by the Department.

Section 236(a) of the INA (discussed further below) provides for the arrest and detention “[o]n a warrant issued by the Attorney General [AG]” of an alien pending a determination of whether that alien should be removed from the United States. Section 287(d) of the INAstates:

Detainer of aliens for violation of controlled substances laws

In the case of an alien who is arrested by a Federal, State, or local law enforcement official for a violation of any law relating to controlled substances, if the official (or another official)-

(1) has reason to believe that the alien may not have been lawfully admitted to the United States or otherwise is not lawfully present in the United States,

(2) expeditiously informs an appropriate officer or employee of the Service authorized and designated by the Attorney General of the arrest and of facts concerning the status of the alien, and

(3) requests the Service to determine promptly whether or not to issue a detainer to detain the alien,

the officer or employee of the Service shall promptly determine whether or not to issue such a detainer. If such a detainer is issued and the alien is not otherwise detained by Federal, State, or local officials, the Attorney General shall effectively and expeditiously take custody of the alien.

As the foregoing demonstrates, section 236 of the INA is more general, while section 287 of the INA is more circumscribed and intended for the specific benefit of other federal agencies, states, and localities. Neither of those provisions provides for, or more importantly requires, a “judicial warrant”, however.

In fact, section 236 of the INA specifically references a warrant issued by the AG, now the Secretary of Homeland Security. The regulations specifically stipulate who may issue such a detainer:

(1) Border patrol agents, including aircraft pilots;

(2) Special agents;

(3) Deportation officers;

(4) Immigration inspectors;

(5) Adjudications officers;

(6) Immigration enforcement agents;

(7) Supervisory and managerial personnel who are responsible for supervising the activities of those officers listed in this paragraph; and

(8) Immigration officers who need the authority to issue detainers under section 287(d)(3) of the [INA] in order to effectively accomplish their individual missions and who are designated individually or as a class, by the Commissioner of CBP, the Assistant Secretary for ICE, or the Director of the USCIS.

Again, there is no regulatory provision for a federal judge to issue a detainer, let alone a warrant.

Notably, the new detainer form (I-247A) specifically states “DHS HAS DETERMINED THAT PROBABLE CAUSE EXISTS THAT THE SUBJECT IS A REMOVABLE ALIEN,” and is signed by the appropriate immigration officer. Not a “belief” — probable cause.

A review of the foregoing provisions indicates that, with the specific exception in section 287(d) of the INA, neither explicitly authorizes detainers (nor do they prohibit them) but the regulations plainly do authorize the issuance of detainers. As Cadman has noted, however, detainers “are — and have been for generations — a standard protocol for asking cooperation from law enforcement agencies when seeking to take custody of aliens.” He continues:

What’s more, the filing of detainers, colloquially known as “holds”, is a standard practice throughout U.S. law enforcement at every level. Virtually all agencies seek such assistance from one another, knowing that if the system of cooperation breaks down, then all public safety is compromised.

Could you imagine how difficult it (and dangerous) it would be if, say, the FBI had to get a judicial warrant in order to put a hold on a suspected terrorist in state or local custody?

Cadman’s post specifically related to an order that was issued by Judge Michael Baylson of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in City of Philadelphia v. Sessions, which had to do with the provision of funding to states and localities that did not comply with certain conditions related to immigration enforcement imposed by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) under the federal Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program (“Byrne JAG”).

Judge Baylson issued a memorandum adding to his final judgment (holding that DOJ could not condition those grants) to provide for the following:

To the extent an agency of the United States Government has probable cause to assert that an individual in the custody of the City of Philadelphia is a criminal alien (as previously defined by this Court in City of Philadelphia v. Sessions, 2018 WL 2725503, *n. 3, (E.D. Pa. June 6, 2018)), and seeks transfer to federal custody of such individual within a city facility, it shall secure an order from a judicial officer of the United States for further detention, as allowed by law.

He did not include a mechanism to “secure an order from a judicial officer of the United States” in that memorandum and, as noted, none is apparent. Or, as Cadman noted:

Exactly what kind of “court order” are ICE agents to seek when asking authority to detain an alien? There is no provision in the INA — no provision whatsoever — for judicial orders. Nor do they exist in any other federal statute. What the INA does specifically provide for is arrest of aliens, with or without warrant, for violations of the immigration laws — but the warrants authorized by Congress are not judicial warrants, and deliberately so.

He specifically referenced sections 236(a) and (c) of the INA, which state:

(a) Arrest, Detention, and Release.

-On a warrant issued by the Attorney General, an alien may be arrested and detained pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed from the United States.

…

(c) Detention of criminal aliens.-

(1) Custody. The Attorney General shall take into custody any alien who [is inadmissible or deportable for criminal offenses defined under several sections of the INA] when the alien is released, without regard to whether the alien is released on parole, supervised release, or probation, and without regard to whether the alien may be arrested or imprisoned again for the same offense. [Emphasis added.]

Cadman continued:

There is absolutely no reference in any of the above citations for a need to present …please read the rest here from CIS.

By D.A. King

https://vimeo.com/showcase/gasenpubsaf

THE BASICS ON ICE WARRANTS AND ICE DETAINERS

Why ICE is Sending Immigration Warrants to Local Law Enforcement and What it Means

Q: Where does ICE’s authority to issue a detainer stem from?

A: By issuing a detainer, ICE requests that a law enforcement agency notify ICE before releasing an alien and maintain custody of the subject for a period not to exceed 48 hours, excluding Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays, to allow ICE to assume custody. This request flows from federal regulations at 8 C.F.R. § 287.7, which arises from the Secretary’s power under the Immigration and Nationality Act § 103(a)(3), 8 U.S.C. 1103(a)(3), to issue “regulations … necessary to carry out [her] authority” under the INA, and from ICE’s general authority to detain individuals who are subject to removal or removal proceedings.

–>Required reading for Georgia legislators.

________

The below is taken from the March 14, 2024 hearing on HB 1105 in considering HB 1105. Committee members are listed here.

HB 1105 – The Georgia Criminal Alien Track and Report Act of 2024

Video of entire committee meeting here. *See March 14, 2024

* We note that this hearing was held three weeks after the murder of Laken Riley in Athens.

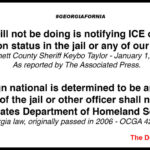

The Senate version of HB 1105 changed language that required Georgia jailers to comply with ICE detainer notices and inserted ACLU-ish anti-enforcement language that would require a judicial warrant. The below is the Chairman alluding to a mistake his office made in that replacement langauge that gutted the bill. There are other changes that watered down measure as well.

Chairman John Albers:

“Uh, I know there are some people watching online. Uh, we worked very hard on this bill for the last week and a half. Uh, we got a lot of input, very thoughtful. I will tell you, there are some people that think it’s not going to, or not gone far enough, and we got some people that think the opposite. We tried to craft something in the middle, and I for one, and I know you gentlemen do too, believe that word “compromise” is not a dirty word, it’s a good word, and we should do it more often in order to, uh, get consensus.

Uh, I think this is a very well-balanced bill. I wanna thank you for your help on that. At the appropriate time there are two amendments that are gonna be offered. One is a scrivener’s error that I will tell you all about right now, and it’s gonna be, uh, between lines 273 and 274, where it says, “An a rent- arrest warrant issued by.” That actually, from where it’s, “The United States,” to the next line, “Homeland Security,” should actually be, a federal judge, or federal magistrate judge, is that correct, Jenna?

Jenna – Legislative Counsel:

A federal magistrate.

Chair Sen. John Albers responding to a shocked gasp of “no!” from a pro-enforcement activist sitting in the front row:

“I’m sorry. That’s gonna be what’s gonna happen. So that is one area, uh, because those folks cannot take out warrants.”

Chair Sen. John Albers:

Uh, and then, uh, there will be another, uh, amendment that’s gonna be offered by Senator Bearden, and I’m gonna let him bring his amendment up after that, uh, as well. So I just want to tell everybody what’s gonna happen here. Um, we’re gonna do, uh, any final questions-…”

_____

The text of this part of the bill now reads like this:

270 – No person identified by the LESC of the United States Department

271 of Homeland Security pursuant to this subsection shall de detained unless a request to

272 detain has been received pursuant paragraph (2) of this subsection or the existence of

273 an arrest warrant issued by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement

274 Division of the Department of Homeland Security a federal judge, or federal magistrate for each person verified.

By D.A. King

A face for radio on the radio!

My old friend Izzy Lyman is a regular guest host for Trucker Randy on his Patriot Voice Radio Network show from beautiful N.W. Michigan. Izzy wanted to know about the current situation in Georgia. So I told her.

By Fred

We are sorry to inform you that D.A. King, President and founder of the Dustin Inman Society, has left us.

Donald (“D.A.”) Arthur King, 1 April 1952 – 5 March 2025.

D.A. King left this life and his work for the nation that he loved, confident that he has done his best. D.A. passed on peacefully after a private battle with cancer.

“Once a Marine, always a Marine” – D.A. was always visibly proud of his service and his honorable discharge from the U.S. Marine Corps (1970-1976).

D.A. described himself as “pro-enforcement” on immigration and borders, an issue on which he dedicated the last 21 years of his life as an expert activist, writer and public speaker.

Contact info for the Georgia delegation in Washington DC here. Just click on their name.

You must be logged in to post a comment.