Why Isn’t Anyone Talking About the Most Important Border Law?

The Secure Fence Act of 2006 isn’t just about fences — it mandates that DHS prevent all illegal entrie

Center for Immigration Studies

The Southwest border, which prior to January 2021 was in pretty good shape, is teetering on dissolution due largely to President Biden’s ham-handed rescission of nearly all of the policies his predecessor implemented to deter illegal migration there. States have sued (thus far, successfully) to block Biden from rescinding the most effective of those Trump policies, but for some reason neither they nor reviewing courts have paid attention to the most important border law — the Secure Fence Act of 2006.

Background on the Secure Fence Act. Its title notwithstanding, the Secure Fence Act is not just about building fences at the border, although that is what it is best remembered for.

Rather, the fences and other infrastructure that the bill authorized and mandated were intended to be just a part of a regime to secure the nation’s borders, and in particular the Southwest border. That’s not to say that the Northern border was given short shrift, but the bill simply authorized a study of the need for and feasibility of erecting infrastructure along the 49th parallel, it did not mandate construction there.

By contrast, the Secure Fence Act was rather exacting (and specific) when it came to “fencing and security improvements” between the Gulf and Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

The bill identified five different areas at the Southwest border where Congress required DHS to construct at “least 2 layers of reinforced fencing, the installation of additional physical barriers, roads, lighting, cameras, and sensors”, and specified two “priority areas” for expedited attention.

Again, however, that border infrastructure was just a means to an end — not an end in itself. Congress’s end, identified in Section 2 of the bill, was “achieving operational control on the border”.

The “Operational Control” Mandate. What is “operational control on the border”? Section 2(b) of the act defines it as “the prevention of all unlawful entries into the United States, including entries by terrorists, other unlawful aliens, instruments of terrorism, narcotics, and other contraband”. (Emphasis added.)

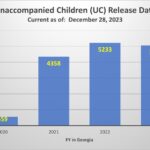

Given the fact that Border Patrol agents at the Southwest border were so overwhelmed apprehending, processing, and caring for more than 1.659 million illegal migrants in FY 2021 (an all-time record) that more than a half-million others “got away” and entered the United States illegally, preventing the “unlawful entry” of any illegal migrant might seem like a purely aspirational pipe dream.

But it’s not. It is a congressional mandate that the secretary of Homeland Security is required to meet under Section 2(a) of the Secure Fence Act, which states as follows:

Not later than 18 months after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Secretary of Homeland Security shall take all actions the Secretary determines necessary and appropriate to achieve and maintain operational control over the entire international land and maritime borders of the United States.

The Secure Fence Act of 2006 was enacted on October 26, 2006 (I described the entire legislative history of the bill in an August post), which meant that then-DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff had until April 26, 2007, to meet that “operational control” goal.

That said, the mandate did not end on April 26, 2007. It is ongoing and has bound Chertoff and his five permanent (and numerous acting) successors, up to and including current DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas.

There is no “sunset provision” in the Secure Fence Act that would have repealed that mandate at a date certain, or after operational control was achieved once.

In fact, the Secure Fence Act requires the DHS secretary to submit a report “on the progress made toward achieving and maintaining operational control over the entire international land and maritime borders of the United States in accordance with” Section 2 therein annually. If Mayorkas has not simply blown off that requirement, that is one report I would love to see.

To be clear, Section 2 of the Secure Fence Act mandates that Mayorkas “take all actions” he has to in order to “achieve and maintain operational control over the entire international land and maritime borders of the United States”, that is, to prevent even a single alien from entering the United States illegally. More than 500,000 got-aways proves that he is failing to do so.

Of course, it is not just those 500,000 got-aways who have entered the United States illegally. Mandatory court filings in Texas v. Bidenreveal that the Biden administration has released hundreds of thousands of illegal migrants CBP has apprehended into the United States in recent months. Every one of those releases is also in violation of Section 2 of the Secure Fence Act of 2006.

Why The Secure Fence Act Matters. So, why does a 15-year-old (plus) bill matter in 2022?

To explain, it is important to note that the Secure Fence Act focuses exclusively on operational control of the border, not on DHS’s actions in any given case.

Biden’s DHS contends that it has the authority to simply release any illegal migrant that it apprehends at the Southwest border in the exercise of its “prosecutorial discretion”. That is, at best, a questionable proposition, given the fact that “prosecutorial discretion”generally refers to the power of the state to “prosecute” an offense, or not.

As ICE’s legal branch (somewhat self-servingly) explains the concept, “prosecutorial discretion” is “the longstanding authority of a law enforcement agency charged to decide where to focus its resources and whether or how to enforce the law against an individual”.

With respect to all those hundreds of thousands of aliens apprehended at the Southwest border, DHS does not really have the discretion not to prosecute them — they are by statute “applicants for admission”, and either DHS or the immigration courts have to decide whether they will be admitted.

But even if DHS had the discretion to decide how and when to make that admission determination, “prosecutorial discretion” does not extend to a decision to release them en masse as it is doing now. Congress has already made clear that they must be prosecuted to determine whether they should be admitted. At that point, I would argue, “prosecutorial discretion” ends.

Why would I argue that? Because Congress has also mandated that illegal migrants be detained while that admission determination is being made, negating any claim that “prosecutorial discretion” allows DHS to release aliens seeking admission, except for one at a time on “parole”. But even that authority is tightly cabined statutory discretion, not “prosecutorial discretion” per se.

Assuming, however, for the sake of argument, that DHS has the discretion to prosecute illegal migrants (or not) and to release them (or not), remember how ICE’s lawyers described “prosecutorial discretion” above — the authority to decide “how to enforce the law against an individual”?

The “operational control” mandate in the Secure Fence Act of 2006 is not amenable to any such “prosecutorial discretion”,… read there rest here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.